La Primavera En El Norte

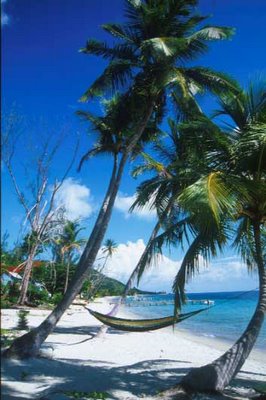

Last week I was in desde Desdemona squinting at the sun. The bay was turquoise. Butterflies swarmed. Then I returned to upstate New York. There was no snow. But there was also no color. No green. But regardless, and to my relief, Spring may be beginning.

Last week I was in desde Desdemona squinting at the sun. The bay was turquoise. Butterflies swarmed. Then I returned to upstate New York. There was no snow. But there was also no color. No green. But regardless, and to my relief, Spring may be beginning.The signs are clear. Redwing blackbirds always return during the first round of March Madness, blowing their whistles, calling fouls. Then robins. Geese fill the sky migrating back to Canada. Daylight savings time begins tomorrow. And tonight, mirabile dictu, at last the sound of the peepers. Not yet a whole celestial choir calling out all night long. Just a few singers. The Spring Peeper (Pseudacris crucifer) is pictured. And its calling is the surest sign of the arrioval of spring to these frozen places.

How strange. A few days ago in desde Desdemona I saw a bird I had never seen before. It was outside the kitchen window sitting on a bush. And it looked like this photo.

This, I thought, is not something one sees in the Hudson Valley. Its color was so bright it was hard to believe it was real. And, I thought, this is possible only because of the bright, bright sun that makes me squint, and the clear Caribbean and the wild colors of the flowers and trees and fruit. And the millions of butterflies. And the way the inside of a papaya is bright orange and the way the inside of a mango is yellow yellow.

This, I thought, is not something one sees in the Hudson Valley. Its color was so bright it was hard to believe it was real. And, I thought, this is possible only because of the bright, bright sun that makes me squint, and the clear Caribbean and the wild colors of the flowers and trees and fruit. And the millions of butterflies. And the way the inside of a papaya is bright orange and the way the inside of a mango is yellow yellow.I want my life to be like this Hooded Oriole. I want my life to be, as Paul Simon wrote, bright like Kodachrome. I don't mind squinting. You remember how it goes: "Kodachrome/You give us those nice bright colors/You give us the greens of summers/ Makes you think all the world's a sunny day, oh yeah!/I got a Nikon cameraI love to take a photograph/So Mama, don't take my Kodachrome away."