I’m not the first 59-year old man who’s been arrested for something other people think is stupid. And I’m not the first by any means to fake remorse, or to say with false contrition that what I did was wrong. But the truth is something entirely different.

For my entire life I have been afraid of heights. As a kid, I’d only climb to the first big limb of a tree, and only then if the branches were low. I didn’t like climbing over fences. Later, I’d stand back an arm’s length from wobbly railings that overlooked motel parking lots. I’ve studiously avoided the Empire State Building observation deck, though I’ve lived near it for my entire life. I once ate at the Windows on the World Restaurant once, but I sat with my back to the view. I did walk across the roof of the Duomo in Milan and climb up a tall ladder at Bandilero in New Mexico, but I don’t understand how I accomplished these aberrations.

So when the 200 year old church in town decided to repair its steeple, I paid no real attention to it. I did notice that the steeple seemed to be tilting ever so slightly, probably because of rotted timbers, and that some day it might decide to plunge through the abyss and into the tiny town square below it. But considering the few people who live in our town, the even smaller number who ever enter the park, and the remote chance that anyone would actually be hit by the plunging, 2 century old steeple, I didn’t think the repairs were needed for at least another decade or two. There was no real emergency. The members of the church apparently felt differently.

About a month ago, they put up a gigantic, metal scaffold that towered in front of the church and extended to the middle of the high steeple. And it wasn’t like those ones you see in cities with narrow ladders and thin walkways. No. It had metal stairs that ascended from the sidewalk all the way to the top. And, more amazing, when the workers went home for the day, they didn’t remove the stairs, or post signs, or hire a cop to prevent access to the Tower of Babel. Any lunatic who wanted to could climb to the top and jump.

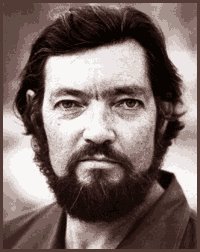

A couple weeks ago, I drove past the tower in the early evening. The windows of my car were down. Birds were singing, the breeze was warm. There was a bearded man standing near the entrance to the scaffolding. I wondered whether he would be the person to shatter our sleepy town’s tranquility by diving from the steeple into the park. I wondered if he would leave a note explaining his despair. I wondered whether there might be literary allusions in his suicide note to the painting of a similar steeple in

Empire Falls, or cinematic ones to the climbing of the water tower in

Gilbert Grape. Or whether he was so impatient to embark on his final swan dive that he would leave only incoherent rambling on the envelope of an overdue electric bill. Or worse, no note at all. I didn’t think he looked particularly distressed, I didn’t stick around to see how his suicide would unfold.

That night I had a dream. In the dream I learned that there were “portals” I could enter, and that in them I’d find various stories. In some, I’d find just shreds of a story, a snippet, a paragraph. But in others I’d find stories so elaborate, so complete, so ingeniously constructed that all I would have to do was pull gently, as if the story were wool yarn, and I would receive a complete novel. It would be easy. If I found the first sentences in the portal, and pulled on them, the next 120,000 words attached to it were sure to follow.

And where are these portals? They’re everywhere. I found one walking in a field with the dog, and I found another in the city while I was waiting for a light to change. You just step into them and see what story is in them. You have to remember the first sentences when you leave the portal, so you can retrieve the complete story. I don’t know whether the portals move around, or whether you can find them at the same place at a later time, if you forget the first sentence, or the strand somehow breaks.

Yesterday in the early evening, I went for a walk to search for some portals. I didn’t find any good ones near the house, so I thought I’d walk into town and look around. I was carrying with me in a backpack my 10-year old laptop. The idea was that when I found a really good portal, I’d take down the first 3 or 4 sentences before the ancient battery gave out. Later, I’d have access to the entire story, and I’d have a new book, a novel, in record time and with little effort.

When I got to the Tower, I thought I might as well step over the three pieces of ratty duct tape blocking access to the stairs and sample the portals at the front of the 250 year old church. I had no intention of climbing higher than 10 feet. In fact, the prospect of climbing higher than the middle of the first floor windows filled me with dread. But I didn’t find any portals I liked on the first level of the scaffold. So I continued on.

Eventually, on the top floor of the scaffold, I found a portal that was simply incredible. It held an amazing, long, complicated story of love, sorcery, intrigue, devotion and enlightenment. I had been crawling on my knees on the metal for what felt like hours before finding this portal. I was afraid to look down from the scaffold: I was high in the air, next to the leaning Tower, the earth was far, far below. When I tried to get out my laptop to record the first few sentences of the story, my laptop slipped out of my backpack, slid across the metal floor of the scaffold, and fell into the open space. I watched as it plummeted to earth, and I watched as it crashed through the front windshield of an SUV belonging to the Sheriff’s Department.

The deputy was standing outside the SUV looking up at me when the laptop hit. He, apparently, had been summoned by neighbors who called 911 to say that a lunatic, me, was climbing on the scaffold and might be planning on jumping to his death. How anyone could believe that someone, in this case a 59-year old man, who was afraid to stand up and was crawling on the scaffolding, was going to jump is beyond me. Nor do I understand why the deputy may have felt that I was trying to drop a heavy, decade old laptop computer on him. Or trying for some bizarre reason to destroy his patrol car. Everyone knows I have no animosity toward law enforcement and despise acts of violence.

The worst part of all of this isn’t my embarrassment at being arrested, or the arrest report in the local police blotter, or having to appear before the town judge, or appearing to dispassionate observers to be a crackpot or eccentric or lunatic. No. The worst part is that tonight I have to sneak back to the portal, this time with a Moleskine notebook and a pencil, to retrieve this astounding story. And I have to do it before they move the scaffold or disturb the portal. So tonight, Saturday night, even though it’s raining and cold, I have to wait until after dark, again pass the duct tape, again climb the scaffold, again crawl on my hands and knees to the portal, and take down the first paragraph.