sábado, septiembre 30, 2006

viernes, septiembre 29, 2006

Why We're Not Complaining

From The Writers' Almanac:

Today is believed to be the birthday of the man who's generally credited with inventing the modern novel, Miguel de Cervantes, born near Madrid (1547). He was one of the unluckiest authors in the history of Western literature. In 1570 he enlisted in the army in order to help fight back the invasion of the Ottoman-Turkish Empire. He fought bravely in a battle off the coast of Greece, even though he was shot twice in the chest and once in his left hand. The battle was a victory, and he became a war hero, receiving special recognition from the king.

Unfortunately, he and a group of other military men were captured by Algerian pirates on the way home from the war. They were held for ransom in North Africa for five years. Cervantes led four escape attempts and all four attempts failed. As punishment for his escape attempts, he was chained to a wall for months at a time.

When he was finally ransomed and returned to Spain, Cervantes assumed that since he was a famous war hero, he would have no trouble getting government work when he got back to Spain. But nobody even remembered the battle he had fought in. The Spanish economy was in terrible shape, and it was nearly impossible to find a decent job. So he began writing plays. He knew he had to work quickly in order to make his name, and so in the course of just a few years, he managed to produce more than 30 plays.

But not one of Cervantes's plays was a success. As a desperate measure, he took a terrible job as a kind of a tax collector. He had to travel around the countryside in all kinds of weather, arguing with shopkeepers and farmers, enduring accusations of corruption everywhere he went. Even priests hated him. He was excommunicated by half a dozen churches. He was in his 50s, barely supporting his family, unhappy in his marriage, and failing to achieve success as a playwright or poet.

Then in 1595, he got caught up in a financial scandal. He was charged with embezzlement, even though historians believe that he was probably one of the only honest employees working for the government at the time. Having escaped five years of captivity in Africa, Cervantes now found himself imprisoned in his own country for a crime he didn't commit.

Cervantes later wrote that it was during that time in the Royal Prison of Sevilla that he first had the idea for his masterpiece, Don Quixote (1605). He conceived of it as a parody of the chivalric romance genre, which was popular at the time. And so Cervantes invented the character of Don Quixote, a middle-aged man who has read so many romances that he comes to believe they are true. He embarks upon a career as a knight, fighting for righteousness and for the love of his lady, Dulcinea del Toboso, who is actually a peasant wench. He takes as his squire a farmer he knows named Sancho Panza, and the two go off to engage in jousts with windmills.

The first volume of the novel was a best-seller, but unlucky as always, Cervantes didn't make much money from it. There was no copyright at the time, and pirated editions were published all over Europe.

Miguel de Cervantes said, "Too much sanity may be madness, and the maddest of all, to see life as it is and not as it should be."

martes, septiembre 26, 2006

The Sky At Night

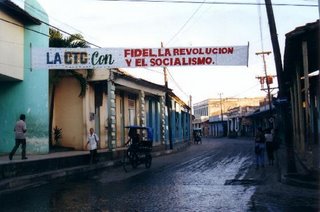

Baracoa, Cuba

Last night before bed I was watching the sky. I saw a meteor. Actually, two. The first was a sudden, bright streak and made me gasp. The second was only faint, like a whisper.

In my dreams last night I travelled again to Baracoa, on the eastern coast of Cuba. Or maybe it was Macondo. I sat on the street playing dominoes and drinking a sip or two of rum and making jokes in Spanglish. The electricity went out as frequently it does. Some people went to find candles. Others like me just sat and stared up at the sky, the Milky Way, the zillion shining stars, the end of the universe. The game stopped; you couldn't see the dot stars on the dominoes. You could only see the sky, and hear the sound of an occasional car.

If people looked up at the stars more often, I thought, how could they fight with each other? Wouldn't they see all of Indra's web and how they were connected to it? Shouldn't the cities of the world occasionally turn off all their lights, so that their inhabitants could see the night sky from the street?

When the electricity returned, interrupting my thoughts, some people clapped. And the radios and TVs cam back on. But I was sad that I had not seen any meteors, and the stars seemed even farther away.

domingo, septiembre 17, 2006

At The Pound

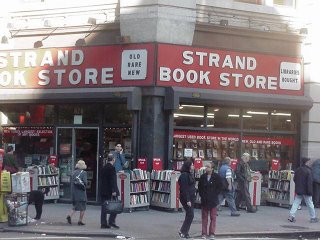

Yesterday I went to the used book sale at Spencertown Academy.

I was overwhelmed by the number of homeless books and people selecting them to bring home. It wasn’t quite like visiting the morgue, though at first I thought it seemed like rows of dead books, a price tag tied to each of their big toes. No, it was more like an orphanage for the mute or a dog pound. The lucky, cute ones are retrieved, lugged to a new home, and end up on a shelf or under the bed, or God forbid, in the trash. And the unlucky ones, what happens to them? What happens to great ones initially purchased as required reading, ignored for semesters, always resold, eventually tattered, on their last legs, trying to look cute at this sale, trying to avoid the land fill?

I didn’t bring anything home. I thought about a not too battered “The Sun Also Rises” and a thin Kawabata with a stiff binding. But I’ve taken a vow of some kind to stop trying to recreate the basement of Strand Books in my house. Only the most indispensible books are coming home with me, and the definition is a moving target that doesn’t expand just because they cost only 25 cents each. I was relieved not to find books by Alejo Carpentier or Carlos Fuentes, books I would have to rescue. I was also relieved not to see a book I wrote in one of the bargain bins, where I would have had to rescue it, or worse, lurk until someone considered giving it a new home and then initiate a sales pitch so that my offspring would find suitable lodgings. "This is an excellent book," I'd say. "Very enjoyable. You'll love it. I do."

I left the sale sad and confused and depressed. I really don’t have room. If I were a book and could talk like one, maybe I could have consoled some of those great novels, Tolstoy and Dickens, for example, who were left behind, the ones whose time has finally come. “Look,” I would have said. “It’s disgraceful. Readers aren’t what they used to be. They cannot appreciate someone as wonderful, as loving, as well crafted as you. It’s not your fault. And owners aren’t what they used to be either. They won’t keep you. That, too, is not your fault. In the name of feng shui or elimination of clutter or God knows what other golden calf, they’re cleansing you without a thought. It’s a really rotten business. It’s not like the old days when once you found a home they respected you and kept you until an estate sale.”

Later that evening my remorse grew. I was walking in Hudson. I saw a used book I myself gave away living on the street, in a free book bin at The Second Show in Hudson, New York. No, I didn’t bring it home again. Seeing it just increased my feelings of morbidity. I made believe it hadn’t been mine and walked down the block in embarassment.

Maybe I’ve been missing the point. Maybe the book is just a body, a container, a husk, and the story is its eternal soul. The books are obviously impermanent. They end up dog eared, in sales, in free book bins and in the land fill. They end up under the bed, covered with dust bunnies. But the story, once its written and told, can go on and on and on. The books, themselves, don’t seem to mind, and in fact, they seem to accept their circumstances. They know it’s not about the preservation of paper and ink and glue, it’s about the stories. If the stories are like trees, why was I yesterday so concerned about the fate of the acorns?

viernes, septiembre 08, 2006

Yet Another 9/11. This One In 1906.

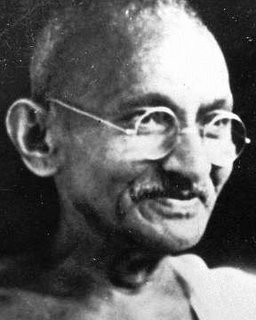

Mahatma Gandhi

On September 11, 1906, Mahatma Gandhi and 3,000 other Indians took a pledge of nonviolence against the discriminatory laws of the South African government. It was the birth of "satyagraha", holding fast to truth, a movement of civil disobedience.

At the time Gandhi was a lawyer in South Africa. Gandhi had launched a campaign to rescue the rights and dignity of 100,000 "free" and indentured Indians in South Africa. He had started the Natal Indian Congress, organized a petition to parliament and founded "Indian Opinion," a newspaper for his movement. But in September, 1906, the Transvaal Assembly introduced the Asiatic Law Amendment Ordinance, which was intended to reduce Indians and Chinese to a semi-criminal status. On September 11, 1906, 3,000 Indians, both Hindu and Muslim, "free" and indentured, gathered at the Empire Theater in Johannesberg to voice their outrage.

Gandhi called on all to pledge non-cooperation with the proposed law, regardless of what penalties they might face, a call for civil disobedience. Then a Muslim merchant, Seth Haji Habib rose and declared that the resolution must be pased "with God as a witness" that Indians would never yield in cowardly submission to such a law. Gandhi realized that invoking God in a politcal struggle would demand steadfast struggle until the end. He was personally willing to take on such a duty.

Twenty years later, Gandhi recalled the moment:

"The meeting heard me word by word in perfect quiet. Other leaders too spoke. All dwelt upon their own responsibility and the responsibility of the audience... and at last all present, standing with upraised hands, took an oath with God as witness not to submit to the Ordinance if it became law. I can never forget the scene, which is present before my mind's eye as I write. The community's enthusiasm knew no bounds."

And so, in addition to everything else, Monday is the 100th Anniversary of 9/11/06, the birth of the Satyagraha movement. Isn't it interesting that the start of this movement was an attempt by the government to crimi nalize minority immigrants?

Credit to Derek Mitchell, Nonviolent Peaceforce, Peacepower, and Michael Nagler for the above information.

martes, septiembre 05, 2006

The Other September 11, The Other 3,000

Salvador Allende (1908-1973)

Vive En Memoria

It was on this day, September 11, 1973, 33 years ago, that democracy died in Chile. A CIA backed coup, led by Gen. Augusto Pinochet, overthrew democratically elected President Salvador Allende and began a repressive, 17 year military dictatorship. Some say that Allende committed suicide during the coup; others, that he was murdered. This event preceded the phrase "regime change" but embodied it.

The BBC put it this way in 1973:

President Salvador Allende of Chile, the world's first democratically-elected Marxist head of state, has died in a revolt led by army leaders.

Air Force planes attacked the presidential palace with rockets and bombs and tanks opened fire after President Allende rejected an initial demand for his resignation.

According to military sources, Dr Allende asked for a five-minute ceasefire in order to resign. But the armed forces said that was impossible because snipers loyal to the president were operating from buildings near the presidential palace.

At least 17 bombs were dropped in an attack on the palace, one of which scored a direct hit.

Martial law has been declared throughout the country, a curfew has been imposed and the carrying of guns has been banned.

Although Dr Allende called on his followers to support him, there appeared to be little organised resistance.

Troops blasted buildings in the city centre around the presidential palace in an attempt to dislodge pro-Allende snipers. Helicopters repeatedly machine-gunned the top floors of buildings near the British Embassy. Bullets ripped through the windows of the embassy - but no-one was reported hurt.

Thousands of workers are said to be marching on Santiago from the north, despite a warning any resistance would be met with air and ground fire.

Opposition to President Allende has been growing for months. He was elected to power in 1970 with only 36% of the vote. He has not held a majority in Congress and gradually his authority has been eroded.

His attempts to re-structure the nation's economy have led to soaring inflation and food shortages. A prolonged strike by lorry drivers who opposed his plans for nationalisation has recently been joined by shopkeepers angry they have nothing to sell.

President Allende brought senior army officers into his government last month in an attempt to head off a revolt.

But the final crunch came three days ago when the two major opposition parties called for the President's resignation. ***

After President Allende's death, General Augusto Pinochet, the Chilean Commander-in-Chief and a leader of the military junta, appointed himself President. His Cabinet was made up almost entirely of military men. Martial law remained in effect. Troops patrolled the streets. Dissenters were disappeared. Bodies piled up in the streets and the soccer stadium.

President Allende's widow and a number of his other supporters were granted political asylum in the Mexican Embassy and flew to Mexico five days later.

Pinochet's regime was characterised by brutal repression and more than 3,000 people were killed or disappeared during his 17 years in charge. He was arrested in London in 1998 for human rights abuses but after a protracted legal battle he was ruled unfit to stand trial.

And so, in Chile, a different, sad 9/11, one which our Government would just as soon have us forget. But it's a 9/11 I hope you will pause today to remember, as I do.

I think of Allende and Neruda drving around Chile campaigning. Allende sleeps between the frequent stops. Neruda stares out the window and scribbles. After Allende speaks of politics to small groups of villagers, Neruda, who had by then won the Nobel Prize, reads his poems to them. I imagine that Allende and Neruda are weary but happy. I imagine that they smile and are thankful that they can bring economic justice to their country. I prefer to dwell on these optimistic images of hope than the violent bombing of the presidential palace by Pinochet's colleagues. I prefer to think of Chile (and the world) like this:

viernes, septiembre 01, 2006

About Labor Day

Does Labor Day celebrate the labor movement in the United States?

Or is it now something else entirely? Just another day off for no real reason, a bookend for the summer, the end of a row of weeks that began with Memorial Day? Is it just about that "final" barbecue of the season? The chances that the team in first place will actually win the pennant? Is it about the closing of the places at the Jersey shore? Is it about some dead, historical movement, somebody else's organization, somebody else's long ago struggle? Is it just historical, a reference to distant things now taken for granted? Things like the 8 hour day, the weekend, overtime, sick leave, workers' compensation, OSHA, you know, things that are now, well, taken for granted? Is it about an organization of which I am no longer a member, but once was? Is it about something my great grandmother belonged to? Or is it something else?

Is it, for example, a reminder of the ongoing struggle to unionize Starbucks by the Industrial Workers of the World?

You know, the Wobblies. That's right. The same organization that gave us Joe Hill and Big Bill Haywood is now slowly organizing Baristas at Starbucks. It's a long, long way from the Haymarket Riots to Starbucks. But on some level it's still there, it's still happening.

It's sad that we tend not to remember where we have been. Or where our parents and grandparents have been. We don't remember the ugly things: child labor, the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, sweat shops, wage slavery, goons. We don't remember how to act collectively. We don't remember what it means to vote for a strike and how it feels to strike. We don't remember not to mourn, to organize. We don't remember to pray for the dead and fight like hell for the living. We don't remember the benefits we receive or how we got them. We cannot recall the enormous cost that was paid. We can't remember the strikes, the arrests, the cops, the skirmishes, the battles, the scabs. We cannot remember the names of people who fought. We cannot remember the rallies and songs. We can't recall the marches and demonstrations. We cannot even remember the picket lines.

We've got amnesia. Wouldn't it be something if we made time on Labor Day, this very Labor Day to think about and remember Unions?