cross posted at

dailyKos

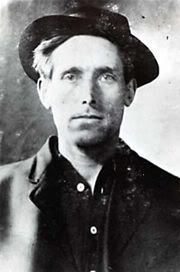

Clarence Darrow (1857-1938)

This is Clarence Darrow, an important American lawyer, a leading member of the American Civil Liberties Union, an agnostic, and the lawyer who defended John Scopes in the Tennessee Monkey Trial in 1925, in which he was opposed William Jennings Bryan.

Why am I telling you these century old stories of American radicals? Why now? It's simple. There is something in this story, as there was in my previous diary about

Big Bill Haywood and Joe Hill and yesterday's diary about

Eugene V. Debs, to inspire us to move beyond our present despair and frustration, something to give us courage. This history, the history of the American left from a century ago, is worth remembering, especially now. I should add that though I might continue the series at a later date, this will be the last diary for now.

I take particular pride in the fact that like me Darrow attended the University of Michigan Law School, and like me, he was unalterably opposed to the death penalty. In fact, throughout his career, Darrow devoted himself to opposing the death penalty, which he felt to be in conflict with humanitarian progress. In more than 100 cases, Darrow only lost one murder case in Chicago. He became renowned for moving juries and even judges to tears with his eloquence. He had a keen intellect often hidden by his rumpled, unassuming appearance. But I want to focus not on death penalty abolition but on his 1925 confrontation with the fundamentalism of the day.

In 1925, Darrow defended John Scopes in the famous "Monkey Trial." You will notice in the trial many of the themes presently repeated by the Christian, fundamentalist right. What you won't notice is that Dayton, Tennessee, in far northeastern Tennessee is about as far now in 2007 from the bastions of metropolitan, secular humanism as one can travel, but that in 1925, it must have seemed to Darrow to be the absolute end of the world, the 1925 equivalent of the reddest of red states.

The Scopes Trial of 1925 pitted against each other William Jennings Bryan and Clarence Darrow in a case that tested a law passed on March 13, 1925, which forbade the teaching, in any state-funded educational establishment in Tennessee "any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals." This has often been interpreted as meaning that the law forbade the teaching of any aspect of the theory of evolution; however, the Butler Act forbade public school teachers in Tennessee from denying the literal, biblical account of man’s origin and forbade teaching in its place the evolution of man from lower animals. For what it was worth, t statute did not prohibit the teaching of evolution of any other species of plant or animal.

During the trial, Darrow requested that Bryan be called to the stand as an expert witness on the Bible. This was quite an unorthodox maneuver. Over the other prosecutor's objection, Bryan agreed. Bryan took the stand and began fanning himself; there was no air conditioning in Dayton, Tennessee in 1925. Many believe that the following exchange caused the trial to turn against Bryan and for Darrow. Personally, I find it an inspiring, remarkably courageous, and very pointed confrontation of fundamentalist beliefs:

"You have given considerable study to the Bible, haven't you, Mr. Bryan?"

"Yes, sir; I have tried to ... But, of course, I have studied it more as I have become older than when I was a boy."

"Do you claim then that everything in the Bible should be literally interpreted?"

"I believe that everything in the Bible should be accepted as it is given there; some of the Bible is given illustratively. For instance: "Ye are the salt of the earth." I would not insist that man was actually salt, or that he had flesh of salt, but it is used in the sense of salt as saving God's people."

Darrow's questions were designed to savage a literal interpretation of the Bible. Bryan was asked about a whale swallowing Jonah, Joshua making the sun stand still, Noah and the great flood, the temptation of Adam in the garden of Eden, and the creation according to Genesis. After initially contending that "Everything in the Bible should be accepted as it is given there," Bryan finally conceded that the words of the Bible should not always be taken literally.

In response to Darrow's relentless questions about whether the six days of creation, as described in Genesis, were twenty-four hour days, Bryan testified, "My impression is that they were periods." Bryan, who began his testimony calmly, stumbled badly under Darrow's persistent prodding. At one point the exasperated Bryan stated, "I do not think about things I don't think about." Darrow responded, "Do you think about the things you do think about?" Bryan responded, to the derisive laughter of spectators, "Well, sometimes."

Both lawyers became sharper and more angry as the examination continued. Bryan accused Darrow of attempting to "slur at the Bible." But he asserted he would continue to answer Darrow's impertinent questions anyway because "I want the world to know that this man, who does not believe in God, is trying to use a court in Tennessee--." Darrow interrupted, "I object to your statement" and to "your fool ideas that no intelligent Christian on earth believes."

Eventually, Judge Raulston cut the questioning short, and on the following morning ordered that the whole session (which in any case the jury had not witnessed) be expunged from the record, ruling that the testimony had no bearing on whether Scopes was guilty of teaching evolution. Scopes was found guilty and ordered to pay the minimum fine of $100.

The confrontation between Bryan and Darrow was reported by the press as a defeat for Bryan. His performance was described as that of "a pitiable, punch drunk warrior." The press in 1925 was not exactly the media of today.

Six days after the trial, William Jennings Bryan remained in Dayton. After eating an enormous dinner, he died in his sleep. Clarence Darrow was hiking in the Smoky Mountains when word of Bryan's death reached him. When reporters suggested to him that Bryan died of a broken heart, Darrow responded, "Broken heart nothing; he died of a busted belly."

A year later, the Tennessee Supreme Court reversed the decision of the Dayton court on a technicality. According to the court, the fine should have been set by the jury, not the judge. Rather than send the case back for further action, however, the Tennessee Supreme Court dismissed the case. The court commented, "Nothing is to be gained by prolonging the life of this bizarre case."

I have tried cases in hostile courthouses in Tennessee and Mississippi, and I am aware of the stress these venues carry, how they are capable of disrupting and undermining even the most carefully planned defense. Because of that, I marvel at the Monkey Trial. Darrow's confrontation of Bryan, even though it was stricken from the record, was so relentless, direct, so grounded, so strong that it turned the tables and made the argument forbidding the teaching of human evolution utterly untenable.

I am filled with admiration and awe for the personal courage it must have taken to bring this off questioning in Dayton. And I'm inspired by Darrow's courage and the skill.

I can imagine that there might be objections to the wider applicability of this story I am telling. You'd be entirely correct to argue that Clarence Darrow was a radical and that he was unique. The world, you might argue, is different now. And the courts and juries are different now, too. Darrow was an declared agnostic, a strong civil libertarian. He defended numerous well known murder cases. He was an outspoken death penalty abolitionist. He was on the left flank of American politics at the turn of the century. And he was one who inspired radical changes in America at the turn of the last century. The objections are that surely, after a century, the same tactics, holding a strong position no matter what, standing up strongly for what is right, just cannot work. To the contrary, my argument is simple: it can. And, in fact, not holding a strong position leads to dilution, disillusionment, despair, and ultimately oppression.

I find enormous inspiration in Darrow. For inspiration in 2007, now, when we so sorely need it, I suggest we continue to look at those on the far, left flank a century ago. That's where the fire is. That's where the inspiration is. And that's where the good changes to our society have always, always come from, from the radical left.

Etiquetas: Clarence Darrow, history, radicals